Victoria May Thatcher

2019-2020

Wood, Ceramic

A Ceramic Heterotopia on Social Architecture, Political Fractures, and Urban Memory

The ceramic sculptural work Victoria May Thatcher by Jonas Vansteenkiste, created during a residency at the European Ceramic Work Centre (EKWC) in 2019, raises questions about how architecture, politics, and memory layer themselves within urban space. By bringing together three influential British women—Queen Victoria, Margaret Thatcher, and Theresa May—in a single title, Vansteenkiste evokes a genealogy of care, alienation, and control in the history of social housing in the United Kingdom.

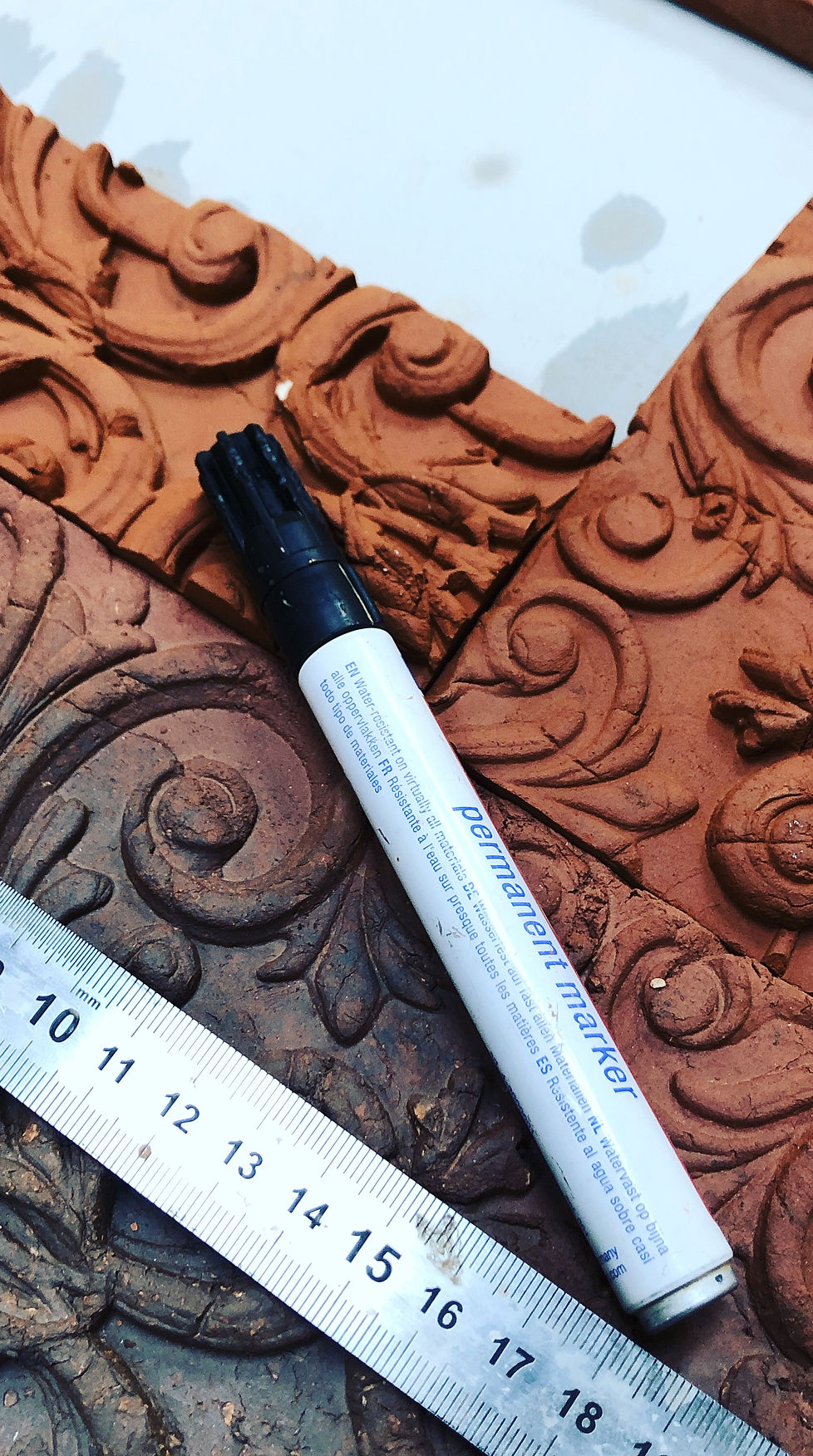

The work is based on a direct experience: in 2016, Vansteenkiste visited Liverpool at the invitation of curator Sevie Tsampalla. The ornamentation of a buildings in the city inspired him to create a mold of a decorative ceramic facade motif. This motif forms the central element of the final artwork—enlarged, exaggerated, and detached from its original context. By positioning it as an obstruction instead of a decoration, it literally blocks access to a home. In doing so, Vansteenkiste transforms aesthetic function into structural critique: the ornament renders living impossible and turns against the notion of “dwelling” as a given.

Victoria: Idealism and the Birth of Social Housing

The roots of British social housing lie in the Victorian era (1837–1901), a period of rapid industrialization and urbanization. Although living conditions in many industrial cities were appalling, philanthropic and socially progressive movements initiated ‘model villages’ and workers' housing that combined hygiene, community, and aesthetics.

Examples such as the Boundary Estate (1893) in London or Port Sunlight (1888), created by soap manufacturer William Lever, show how employers and urban planners tried to realize social stability through well-designed residential neighborhoods. The Arts and Crafts movement, championed by architects like Charles Voysey and William Lethaby, advocated for the integration of beauty, craftsmanship, and social justice.

The ornament that Vansteenkiste found in Liverpool is a direct legacy of this movement: not mere decoration, but an ideologically charged artifact that symbolized the value of the workers' home as a dignified living space.

Thatcher: Dismantling the Collective

Under Margaret Thatcher (Prime Minister from 1979–1990), the social housing system underwent a radical transformation. In line with her neoliberal agenda, she introduced the Right to Buy policy, which allowed tenants of social housing to purchase their homes at a discount. Though initially framed as a form of empowerment, it led to the mass sale of social housing without reinvestment in new construction.

Between 1980 and 1995, over 2 million council houses were sold in England. However, local authorities were not permitted to use the proceeds to build new homes, resulting in a structural shortage of affordable housing and urban decline in many working-class neighborhoods, particularly in cities like Liverpool and Manchester.

After the Toxteth riots in 1981, the Thatcher government commissioned a controversial report proposing a policy of “managed decline” for Liverpool—deliberately allowing the city to wither, with no attempt at recovery or reinvestment (BBC News, 2011).

In Victoria May Thatcher, this moment is palpable in the material language of the work. The ornament becomes a ruinous obstacle; a remnant of a betrayed utopia. The disrupted symmetry and traces of decay in the ceramic embody the failure of a system once aimed at upliftment, now undermined by political ideology.

May: Legacy and Crisis

Theresa May, Prime Minister from 2016 to 2019, inherited not only the chaos of Brexit but also decades of neglect in social housing policy. The most harrowing example was the Grenfell Tower fire (2017), which claimed 72 lives. The disaster was caused by the use of cheap, flammable cladding and the systemic dismissal of residents' safety complaints.

Although the tower itself was built in the 1970s, its maintenance and renovation were carried out under policy frameworks that prioritized cost over safety—an enduring legacy of Thatcher’s dismantling policies and those of her successors. May’s visit to Grenfell shortly after the tragedy was widely criticized; her detached demeanor and lack of direct engagement with residents became symbolic of a broken relationship between government and citizen (The Guardian, 2017).

Vansteenkiste’s work echoes this through the façade-as-mask: an ornament that literally blocks the function of dwelling. This aesthetic of uselessness symbolizes how façade politics—both literally and figuratively—reduced social housing projects to symbols of failure.

Conclusion: The Home as Ideological Battleground

Victoria May Thatcher is not a straightforward indictment but a complex spatial meditation on how politics, memory, and aesthetics intersect. By enlarging the ornament into an obstacle, Vansteenkiste disrupts notions of function, beauty, and access. The work functions as a heterotopia—in the Foucauldian sense—a space where past and present, idealism and ideology, collectivity and exclusion intersect.

What once stood as a symbol of upliftment and care—the Victorian ornament—now becomes a monument to loss. At the same time, it shows the power of material to carry memory and poses the question: who has the right to dwell, and who is excluded—in stone, in policy, in time?

Sources

-

BBC News (2011). Thatcher government considered abandoning Liverpool to 'managed decline'.

-

The Guardian (2017). Theresa May under pressure over Grenfell Tower response.

-

Hall, P. (1988). Cities of Tomorrow. Oxford: Blackwell.

-

Harwood, E. (2010). England’s Post-War Listed Buildings. English Heritage.

-

Atria Knowledge Institute. Repairing the Social Fabric.

a Special thx To:

Curator Sevie Tsampalla, Isabelle Bostyn, Sander Alblas, Ranti Tjan, Nico Thöne, Katrin König, Linda Barkhuijsen, Bianca van Baast, Yves Brandsma, Annette van den Hout, Jorgen Karskens, Debbie Lutter, Monique Ouwers, Leslie Segeren, Tjalling Mulder, Pierluigi Pompei, Marianne Peijnenburg, Peter Oltheten, Rinke Joosten

Photo:Matthias Desmet